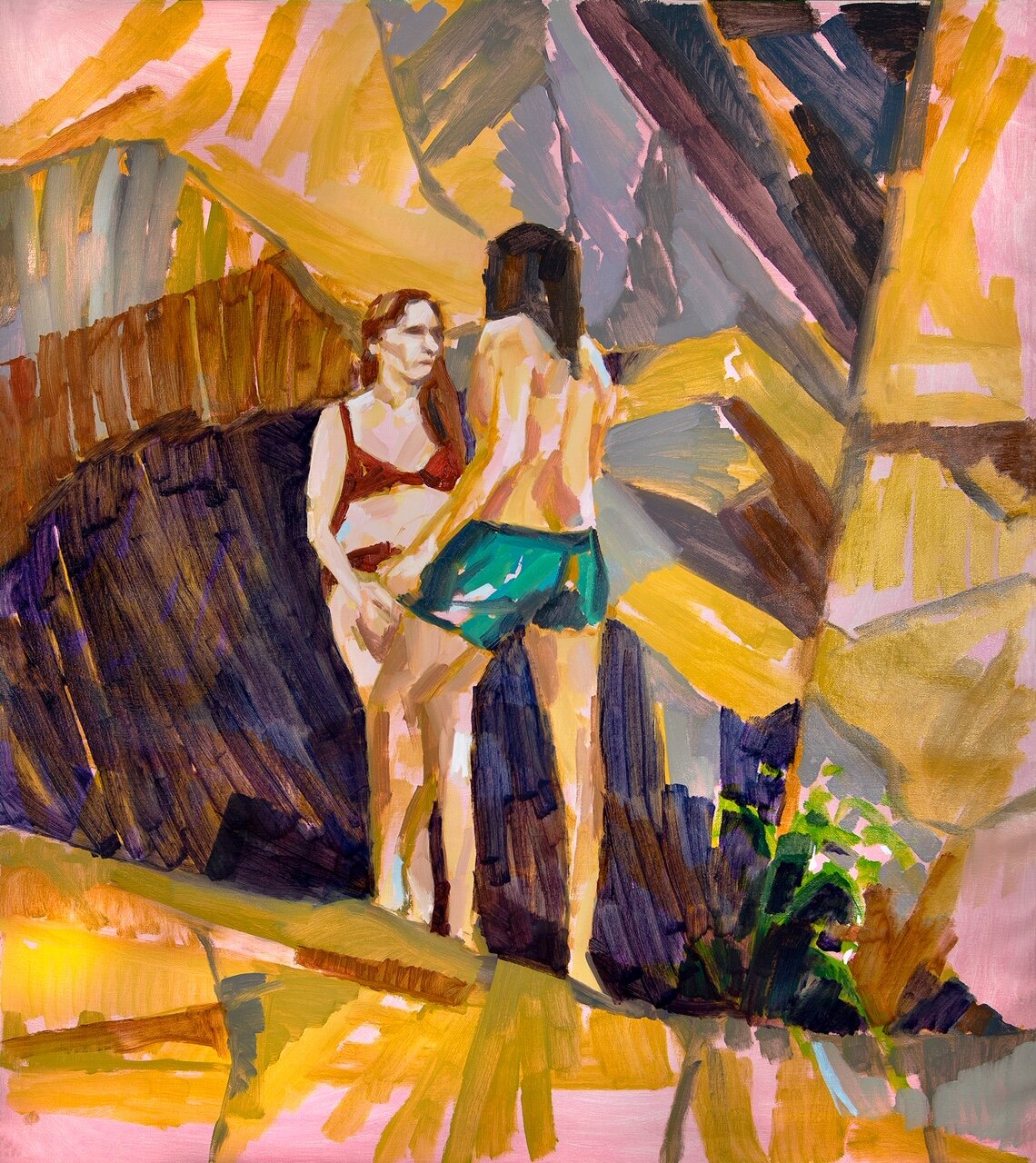

Three palms, oil on linen, 126 x 106 cm, 2020.

T H E F L I C K E R

When Marlowe in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness says: “We live in the flicker – may it last as long as the old earth keeps rolling!”, he is talking about the relationship between time and civilisation. Although the story that follows will be set in Africa, Marlowe is meditating on the Thames. The river has witnessed Britain’s evolution from “one of the dark places on earth” to a land illuminated by a fitful light struck by the Romans and kept alive throughout the middle ages.

For Marlowe all of our civilisation is encompassed by that flickering light which holds the darkness at bay. The tale he tells will reveal the fragility of a world taken for granted, in which the smallest hiatus opens the door for the forces of barbarism. It’s a danger that works on both a public and private level, as a political movement or in the psychology of an individual such as Kurtz, the anti-hero of the novel.

Conrad’s vision is a pessimistic, late imperial one. Throughout the Victorian era the British were haunted by the spectres of great empires of the past, concerned that their own achievements were fated to fall into decadence and ruin. The base assumption was that civilisation represents progress towards a higher state while nature is a blind, dangerous force, “red in tooth and claw”, in Tennyson’s famous words.

Today we display a very different attitude towards nature and the human struggle to subdue its power. As we negotiate a climate crisis of our own making we realise we were wrong to treat nature as an enemy. Perhaps “progress” was not an unalloyed good after all. We may even be able to learn something from those barbarians and savages who were forcibly enlightened (or extinguished) by the imperial enterprise.

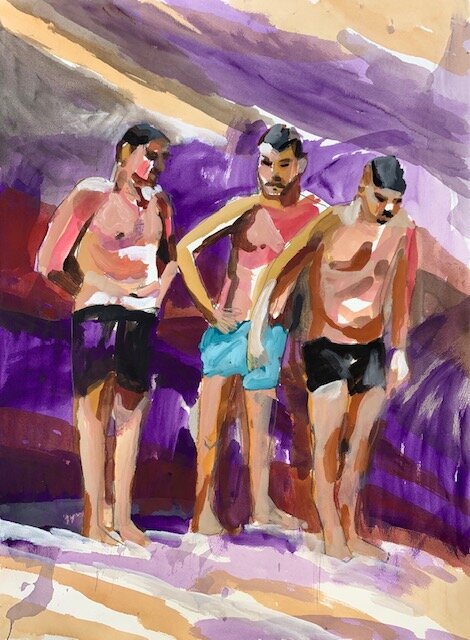

Nick Ferguson’s version of “the flicker” takes Marlowe’s existentially bleak view and gives it a contemporary inflection. In his paintings of people swimming in the tropical waterholes of Northern Australia the artist captures a brief moment of release from the pressures of civilisation, or as he puts it: “a rebellion against the societal drive for productivity and efficiency”.

In Ferguson’s view The Flicker is not a hardwon glimpse of life rescued from nature’s depredations but a pleasurable – albeit brief - surrender to nature. The pale-skinned swimmers in these paintings are doing what indigenous people have been doing for thousands of years, treating these waterholes as a blessed escape from the oppressive heat and humidity. For the tourists it’s also an escape from the pressures of work and the countless small conventions of social status and behaviour.

This sense of release is implicit in the way Ferguson applies the paint, in broad, unfussy brushstrokes. It’s there in the bright pinks, yellows and greens he uses to depict the landscape. In painting the figure he sets out to capture personality in a gesture, a turn of the head or a languid pose. These people are individuals rather than generic types, but not specific subjects for portraiture.

In place of Marlowe’s long, painful struggle of light versus darkness Ferguson presents a flickering moment of freedom snatched from the workaday world – not a universal combat with nature but a hasty, personal embrace. The swimmers in these pictures have rediscovered an instinct that brings them into harmonious realignment with the natural world. Regardless of the darkness Kurtz found in the Congo, in the heart of Northern Australia the depth of a shadow is only a function of the all-encompassing power of light.

Nick Ferguson: The Flicker

Art Atrium, 20 February – 6 March, 2021

John McDonald is art critic for the Sydney Morning Herald & film critic for the Australian Financial Review